Crossing paths with Descartes

Posted on 31 May, 2025

Lately I've been thinking about really fun solutions. You know, those solutions which use some insight you were completely unaware of and make it all look like magic. It's been more than once that I've found myself stumbling into something called combinatorics when trying to learn more about them. On the way to better understanding these combinatorial solutions I've been reflecting on things more foundational. Here, hang on, I'll try to explain what I mean.

Two-up

Two-up is a game played in Australia. Someone tosses two coins in the air, at the same time, and people place bets on the outcome. It is forbidden by law except for one day of the year, ANZAC day. If you want to understand why betting on a coin toss might be outlawed (and otherwise just enjoy a great if but harrowing read) I reckon Wake in Fright is worth your time.

How many possible states can two coins be in? The first coin can be heads or tails, and the second coin can be heads or tails.

| Second heads | Second tails | |

|---|---|---|

| First heads |

|

|

| First tails |

|

|

There are two coins, each with two sides they could land on.

So.

In Two-up two of these possibilities are counted as the same outcome. The order of the coins doesn't matter, which is handy, keeping track of them flying through the air, a few pints deep, would surely be diabolical. So one outcome ends up being twice as likely as the other two. Sounds simple, ends up pretty complicated for John Grant.

Hazard

Hazard is a dice game which was popular in 17th and 18th century England. Someone rolls a pair of dice and places bets on the outcome. The rules for assessing the success or failure of an outcome are fairly complicated. It's referenced in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales in a passage that may have given rise to the idiom "at sixes and sevens", which refers to being in a state of confusion or disarray. I've never read Canterbury tales, I suspect if I tried I'd end up at sixes and sevens.

How many possible states can two dice be in? The first dice can have any one of the numbers one to six face up, as can the second.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

There are two dice, each with six sides they could land on.

So.

As with Two-up, many of these possibilities are counted as the same outcome. All that matters is the sum of the numbers on each dice. So not only is 6 and 4 equal to 4 and 6, but also 3 and 7. But we needn't worry about all that.

DNA

One more game of chance.

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a pretty special molecule. Two chains of smaller molecular units (called nucleotides) each zipped together by the attractive force brought about by electron density being greater nearer to nitrogen or oxygen atoms than hydrogen atoms.

DNA nucleotides all have a deoxyribose component attached to one of four different sub-units (nitrogenous bases): adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine. It's from these we get the letters we use to denote the genetic code: A, C, G and T.

DNA serves multiple purposes. One is as a sort of template that informs protein construction. Proteins are also pretty special molecules, built out of one or more chains (polypeptides) of other molecular units (amino acids).

In 1961 Francis Crick, Sydney Brenner, Leslie Barnett and R. J. Watts-Tobin figured out that this process of protein construction requires that the nucleotides that make up the protein-templating parts of DNA come in groups of three. They called these groups codons.

How many different codons could there be?

There are three 'slots' in each codon, which could each be filled by one of four nucleotide types.

So.

In 1954 Watson and Crick intuited a list of the 20 amino acids believed to be constructed according to DNA's template. They were inspired to do so in response to a tidy, but ultimately incorrect, geometric explanation of the process put forward by a theoretical physicist, George Gamow. Later, in 1956, they came up with their own tidy, but ultimately incorrect, combinatorial explanation.1

This seems like fiendishly complex stuff, there's sure to be many red herrings on the path to the right explanation. I guess that's just how the cookie crumbles.

Quartets

The string quartet has been around as a musical genre and an ensemble instrumentation since the 1750s. In 1825 Beethoven wrote some particularly spicy quartets, numbers 12 to 16, the last major compositions he completed. I love them, though not everyone does. A contemporary of Beethoven, and composer himself, Louis Spohr, described them as "indecipherable, uncorrected horrors."

Three of the quartets, 15, 13, and 14, centre thematically around particular groupings of four notes, groupings united by how far away their constituents are from each other. Which has me wondering what indecipherable, uncorrected horrors might lurk in the collection of all possible voicings a string quartet could play?

First, how many are there? I'm honestly not sure, the ranges of these instruments are a bit flexible, it can depend on the player, whether harmonics are included, the construction of a particular instance of an instrument. I'll use these ranges so we can at least get a ballpark figure.

- Violin

- G3 - A7, 51 notes

- Viola

- C3 - E6, 41 notes

- Cello

- C2 - A5, 46 notes

The first and second violins can each play any one of 51 notes, the viola one of 41, and the cello one of 46. So.

That is a lot.

In space

It's a vast space of possibilities, and Beethoven's four note groupings are in there somewhere, but where? Where, for example, is Cello E4, Viola F4, Second Violin G♯4, First Violin A4? An arrangement of notes played by specific instruments which from now on I will refer to as The Voicing.

It might seem like a nonsense question, but at least it can be answered, and one answer is this: we can think of each instrument as a dimension in space and plot The Voicing within it. Instead of the familiar three dimensions we think of moving about in day to day life, left-right, up-down and forward-backward, we have four dimensions: the cello, the viola, the second violin and the first violin. Because each instrument is constrained in the range of notes it can play we're really talking about some four dimensional shape. We can imagine plotting coordinates within this shape by measuring how far along each dimension a point extends. Starting at 0, being the lowest note that instrument can play, and counting each subsequent note, ending at the highest. I appreciate that counting from 0 might seem odd, but I've spent too much time with computers and it does make some of the following a little simpler.

So, where is The Voicing within that shape? It's at the position: Cello = 28, Viola = 17, Second Violin = 13 and First Violin = 14. And where is that exactly? Well, I can't show you. Unlike the examples of coin tosses, dice rolls or DNA codons, I can't create a visualisation of this space of possibilities. I've never seen any four dimensional things, and I lack the imagination to even try to picture them. What I can do though is change the four dimensional space of possibilities into a different shape and show you that instead.

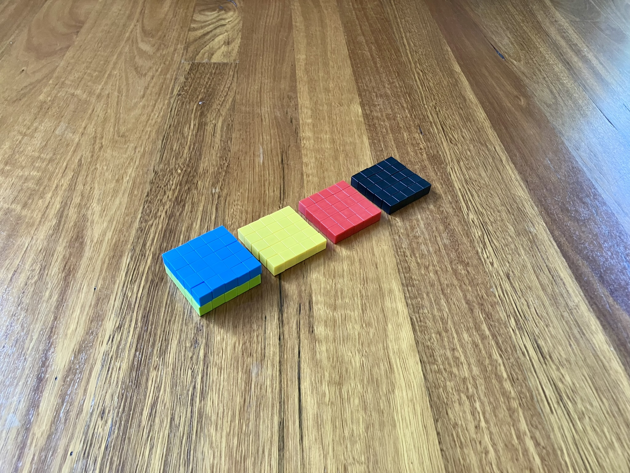

To demonstrate, here's a two dimensional space of possibilities. Perhaps imagine it's a duet of tiny, five tone, glockenspiels.

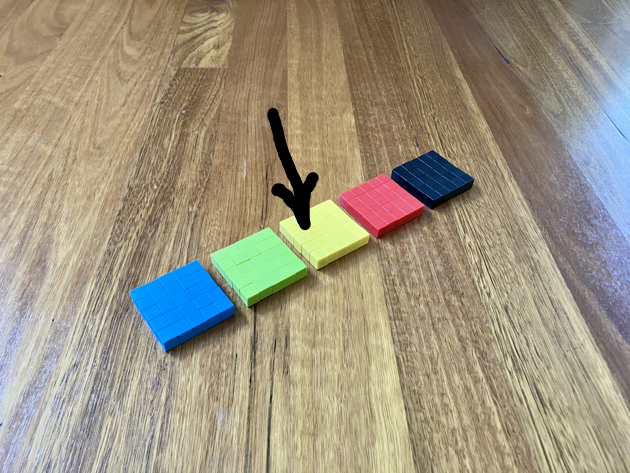

Because this shape doesn't go on forever and I'm not planning on breaking any marbles into pieces two dimensions can be flattened into one by placing each row end to end. A rectangle can become a line.

With this scheme the second yellow marble moves from column 1 row 2 to column 11 row 0. Each marble is being counted, left to right along each row.

In general, columns are counted row number times (in this case 2), then column number is added.

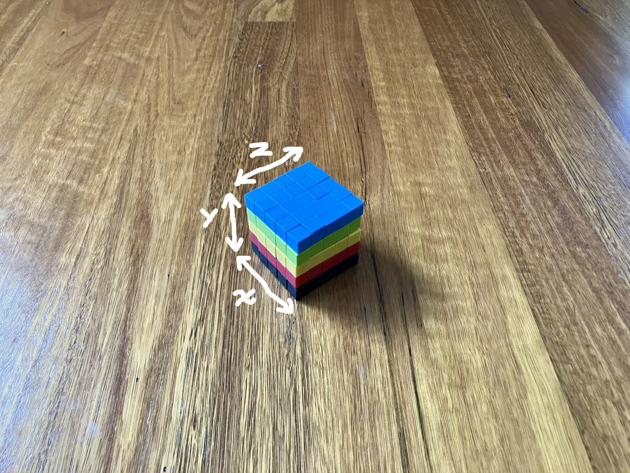

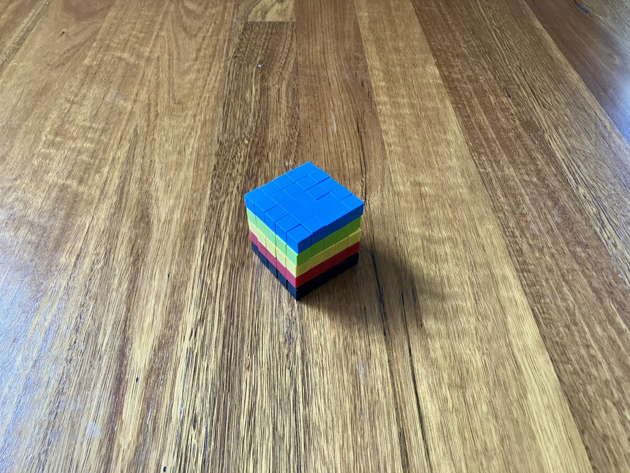

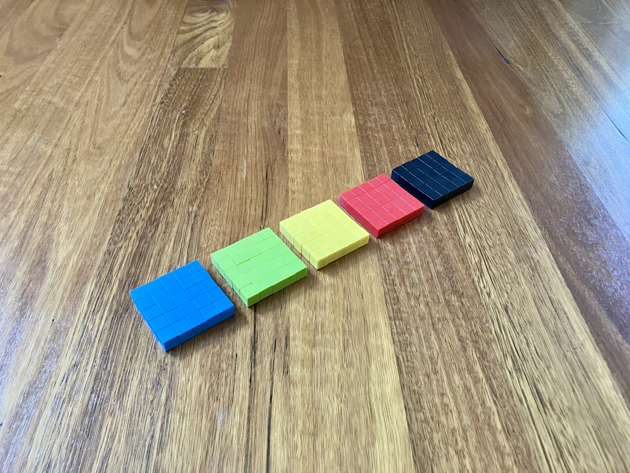

With the addition of another imaginary glockenspiel the same process can be demonstrated in three dimensions, this time labeled , , and .

This three dimensional shape can become a two dimensional shape by unstacking each layer and placing them end to end.

The yellow cube that begins at position ends up at position .

Because the dimension will now always be 0 we can ignore it which allows us to say: position has moved to . More generally we could say: any position has moved to position . Where means: the total number of possible values of . The dimension has now absorbed the dimension.

As with turning two dimensions into one, this counts positions. However here they're not all counted in one go. There's a count per value.

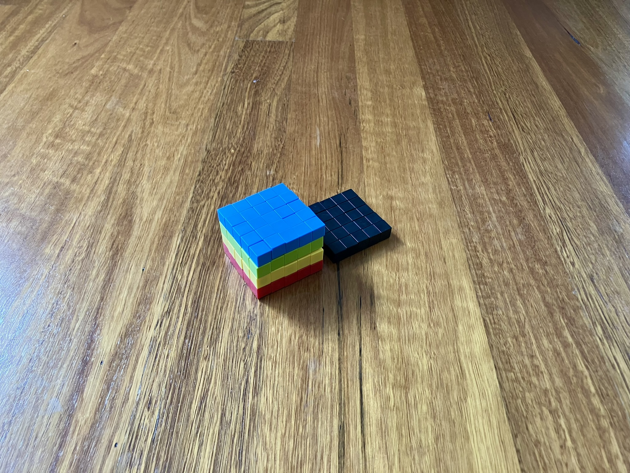

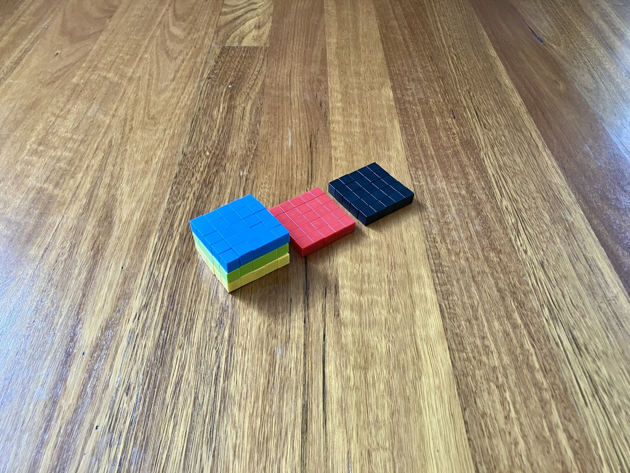

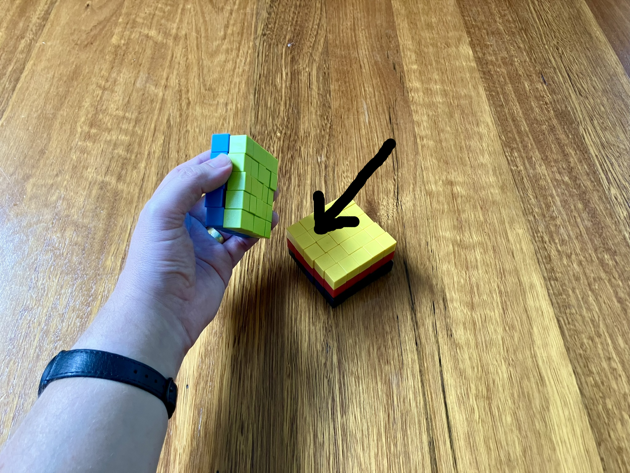

Unstacking the four dimensional shape containing all the string quartet voicings by combining the two violins into one dimension yields a three dimensional rectangular prism of these measurements: Cello = 46, Viola = 41, Violins = 2,601.

Allotting one cubic millimetre to each voicing yields something very roughly the size and shape of one of these standard cuts of timber. (If you look closely you might see a magpie for scale.)

The profile is wrong, it should be nearly square, and it's too short by about 200 millimeters. But it still helps me to look at it and think about what it tells me about the space of possibilities we've been talking about.

Firstly though, what it doesn't tell me is much about The Voicing. It can be found at Cello = 28, Viola = 17, Violins = 677. Which is about where I've placed this marble, except it'd be embedded within the timber, roughly in the centre of the cross-section.

I just don't find it all that enlightening to see. What I do find enlightening is imagining what happens to this piece of timber if we continue this process of unstacking dimensions.

If a three dimensional set of possibilities can be unstacked into a two dimensional set, then we can imagine slicing this piece of timber into one millimeter thin layers and laying them out side by side. If the timber were the right length to begin with we'd have a roughly 2.6 by 1.8 metre rectangular sheet. Which doesn't seem all that surprising to me.

Now, if a two dimensional set of possibilities can be unstacked into a one dimensional set, then we can imagine slicing this sheet into one millimetre by one millimetre pieces of dowel and laying them out end to end. If we did so we'd have a nearly five kilometre long line.

It doesn't change the numbers, but it does change my perspective. It reminds me of how unintuitive it is that each tiny cell in our bodies contains chromosomes that, if unwound, would be two metres in length.

In time

Laying everything out in a line like this is, in a sense, providing a way to visit every possibility in a space. If it were to be stacked back up again we'd have a path which snakes (in this case a very orderly, if but zig-zaggy, snake) through the whole four dimensional shape. Unstacking the whole thing into a line has laid every voicing out in a sequence.

Having this sequence enables us to turn any four note voicing into a single, unique, number between 0 and 4,905,485. For example The Voicing, which, in the space of all string quartet voicings, has the coordinates Cello = 28, Viola = 17, Second Violin = 13, First Violin = 14, becomes 1,371,932.

By referring to the scheme for unstacking shapes explored above it's possible to describe a method for finding the number () of any voicing made up of:

- A note played by the first violin (), from within the set of notes it can play ()

- A note played by the second violin (), from within the set of notes it can play ()

- A note played by the viola (), from within the set of notes it can play ()2

- A note played by the cello (), from within the set of notes it can play ()

Each dimension can be unstacked just as the rows of the five by five grid of marbles were laid out end to end.

Where putting '' either side of the name for a set of things means "the total number of things in the set." For example means: the total number of notes a cello can play.

This allows for counting through all the voicings and it bears a resemblance to how we usually count things. A number such as 1,825 is usually thought of as "5 ones, plus 2 tens, plus 8 hundreds, plus 1 thousand." However it could also be stated as follows.

Which to me looks like successively pushing the ones place to the left, by multiplying by ten, to make room for the next ones value.

This suggests there should be a method for finding The Voicing's number which more closely matches how we talk about everyday numbers, and indeed there is, though it might not look the same at first flush.

It's possible to express the number 1,825 equivalently.

Which suggests that these two expressions are equivalent in general.

What has been arrived at here looks to me like a sort of number system3. One that counts through all the voicings a string quartet can play, just as we might count anything else. What makes this a little more interesting is that it doesn't just count, it encodes. Unlike when counting many things in day to day life, counting these voicings using the method described allows for recovering the original four parts from the single number assigned to them when counted.

To perform this recovery, to decode what was encoded, we need to undo each multiplication and addition which converted the note positions into their corresponding number. To undo one step of multiplication and addition we can use what's called Euclidean division.

If you ever did long division in school, where you figured out how many times some number (the "divisor", ) fit into some other number () with some remainder () left over, you've done Euclidean division. It's division where you end up with a whole number (the "quotient" ), and possibly some remainder; some amount smaller than the number you were dividing by.

Let's say we begin with some number which we know to be made by multiplying some number by some number and then adding some number (which we know is less than ) to that.

This is an abstract form of the numbers we're aiming to decode.

Which can be shuffled around to produce .

And also .

There are several methods to figure out , one is to perform something called floored division which is regular division but the result is rounded down to the nearest whole number. It's written like this.

Floored division discards the remainder, but it can be recovered with one of the above shufflings.

This provides us with a procedure for decoding a number step by step, which goes something like this.

Begin with the number we want to decode.

Then, find the value for , the first quotient, by using floored division with as the denominator.

Which can be used to find , the note the cello plays, by using the shuffling which gave us above.

The first layer of addition and multiplication has now been peeled off.

The process is then repeated beginning from instead of to find , the second quotient.

Which can be used to find , the note the viola plays.

We repeat the process once more to find in order to find , the note the second violin plays.

By finding we've already found the note the first violin plays.

With that we're done.

With this ability to decode ordinary numbers into string quartet voicings it's possible to enumerate all the possible voicings just by counting from 0 to 4,905,485. Doing so sounds like this.

Note without JavaScript you'll get about a six minute sample.

Note if reading on a mobile device you may need to disable silent mode to hear this.

At this speed, ten notes per second, it would take you more than a day and a half of uninterrupted listening to reach The Voicing. I like it. I think it sounds very meditative. Very swoopey.

Turning voicings into numbers has also afforded us the opportunity to be disorderly, rather than orderly, snakes. We can use a non-repeating random number generator4 to erratically jump around, but still visit each and every voicing no more than once. I'm not sure if there's any telling when you'll hit The Voicing, but it's in there. To hear them all, to make sure you've heard the one, would take over five days and sixteen hours.

Note without JavaScript you'll get about a six minute sample.

Note if reading on a mobile device you may need to disable silent mode to hear this.

If I listen for long enough I can talk myself into hearing bass lines and melodies. I think it's sort of fun. Bleep, bloop.

And now here we are at the end, having found some sort of path through an overwhelming space of possibilities. Not only that, along the way we've been able to visit an Australian literary classic, confusing dice games from Early modern Britain, attempts to explain the bewildering complexities of DNA, and some really banging Beethoven. I hope you enjoyed walking it as much as I enjoyed finding it.

Thank you for your time.

Deciphering the Genetic Code: The Most Beautiful False Theory in Biochemistry – Part 1↩︎

I'm sorry, there's already a 'v' and 'w' is just the next letter in the alphabet. If it helps pronounce it "wiola" in your head. Or out loud. Whatever you're up for.↩︎

In this case a Lehmer random number generator.↩︎